Joel Carlson Data Scientist

Machine Learning to Improve Radiotherapy Accuracy

This research was published in Physics in Medicine and Biology - read it here!

Here is the presentation I gave at AAPM 2015 regarding this work:

Radiotherapy plans have become increasingly complex in recent years, and with this added complexity have come numerous new sources of errors during plan delivery. One such source of errors is the multi-leaf collimator (MLC), the final component between the linear accelerator and patient. Tasked with shaping the radiation beam in real-time during delivery, the movement of the MLC must be highly precise. However, due to the highly choreographed nature of MLC movements in modern plans, the beam shapes become slightly deformed, leading to plans not being delivered exactly as intended.

In this project, I used decision-tree regression techniques to predict MLC errors, and incorporated them into the treatment planning system. This research allows treatment planners to view a more accurate representation of the dose as it will truly be delivered to the patient.

Click here to view a web-interface which allows access to the models developed in this work.

Introduction

Before a radiotherapy plan is delivered to a patient, the ability of a treatment unit to deliver to treatment as intended must be verified. To test this, a treatment planning system is used to calculate the dose distribution of the plan on a CT scan of a verification unit (rather than a scan of the patient). Then, a physical linear accelerator is used to deliver the plan to the same verification unit. The calculated dose, and the delivered dose are then compared. If they match closely, then the plan is verified. If there are large discrepancies then actions must be taken to decrease the complexity of the plan. This is a time consuming process, and it is therefore advantageous for the treatment planning system to calculate the dose distribution as accurately as possible. Thus, in this project I used machine learning techniques to improve the calculation accuracy by taking into account the uncertainty in MLC positions.

Background

It is important to understand some of the important components and quantities within the treatment verification process.

Multi-leaf Collimators

As stated above, the MLC is the final component between the linear accelerator and the patient. It is used to shape the beam into the complex shapes required. The MLC used in this study is known as the Varian Millennium 120 MLC, as shown here:

The MLC consists of 120 individual leaves, 60 per side. Each side consists of 40 inner leaves of 5 mm width, and 20 outer (10 per side) 10 mm leaves. The movement of such an MLC is visualized here. During delivery of a plan, the MLC reports it’s real time position in the form of “motor counts”, which can be converted to millimetres using a manufacturer specified and medical physicist verified constant of proportionality.

It has been hypothesized that the MLC is the main contributor of errors which cause plans to fail the verification comparison.

Accounting for differences in planned and delivered MLC positions is likely to be important for increasing the accuracy of dose calculation. The goal, then, is to use any information we can extract from the MLC during delivery to predict errors in positions, and then feed these back to the treatment planning system, so that it may calculate the distributions with knowledge of how the MLC behaves in the real world.

Gamma Analysis

Gamma analysis is one way of interpreting the results of the comparison between planned and delivered dose distributions. It is widely used within radiotherapy, but this comparison is an active area of research.

A detailed description of the method is out of the scope of this article, however the interested reader is referred to Low et al (1998) and Low and Dempsey (2003).

Briefly, there are two numbers to look at, a percent and a distance. The larger the values, the less strict the criteria. That is, \(3\%/3 mm\) is a very loose criteria, and most plans will pass, whereas \(1\%/2 mm\) is quite strict, and many plans fail. Furthermore, the criteria can be calculated with regards to local, or global normalization - with local being the stricter of the two.

A plan will be given a “passing rate” at each criteria, this is a percentage value, and 100% would mean the plan passes perfectly. Practically, anything under 90% passing is getting into questionable territory.

In all cases, a higher passing rate is desirable.

Methods

The goal is to predict errors in MLC positions before the plan is delivered for verification. Thus, we need to extract features from the MLC which may lead to said errors, and are available before the plan is first delivered.

All plans in this study were volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) plans. During a VMAT plan, the head of the linac rotates around the patient, constantly delivering radiation. Internally, the plan consist of a number of “control points”, or angles, at which the positions for each leaf of the MLC are defined. Since there are 120 MLC leaves, and a conventional VMAT plan has 356 control points, we have 42,720 leaf positions per plan to work with. We also know the time between control points, as the head of the linac rotates at a constant speed. Finally, we know the angular separation of the control points is 2.0341 degrees.

Feature extraction

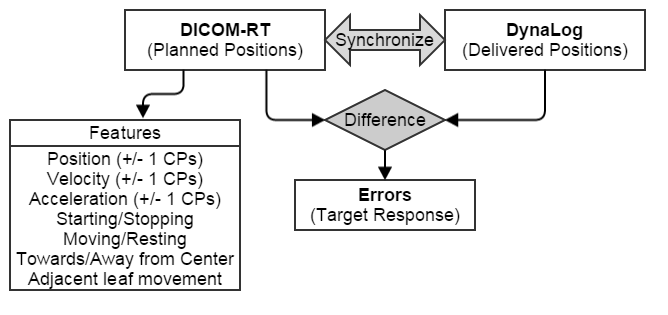

With the above information, I extracted a number of features which may offer predictive ability.

These features were both quantitative, and qualitative. Quantitative features for each leaf included position, velocity, and acceleration at each control point, and the previous and subsequent control points. Qualitative features included whether the leaf was starting or stopping at a given control point, moving or resting, and whether the leaf was moving towards or away from the center of the MLC. These values were also calculated for the leaves directly adjacent to the leaf of interest, under the hypothesis that friction from adjacent leaves may contribute to errors.

This process is outlined in this flowchart:

Training Models

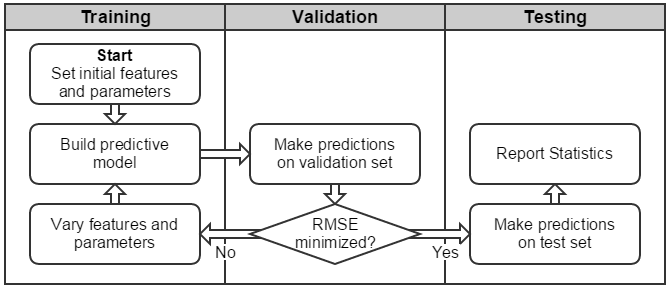

In machine learning, it is good practice to create training, validation, and testing sets of data. The training set is like a sandbox, where you test many tools. The validation set is used to choose the best tool. Finally, the test set is used only after you have chosen the best tool on the validation set. It is on this set which you report the accuracy of your model. In this way, you can be assured that your model is generalizable, and the statistics that you report represent “out-of-box” accuracy.

Since this is a regression task (the errors between planned and delivered positions is a continuous value), the mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean squared error (RMSE) were used to assess model fit. RMSE is used here in place of standard deviation, as the distribution of errors does not follow a normal distribution (the equations are identical, the difference is in interpretation).

The training process is shown below:

Results

Predictive Features

It was found that several of the features extracted were closely related to errors. Leaf velocity is known to be related to errors, as previously published. However, several other features also offered significant predictive ability that had not previously been discovered. Notably, whether the leaf was moving towards or away from the center of the MLC had a statistically significant effect on the error magnitude.

Predictive Accuracy

The mean absolute error magnitude between planned and delivered MLC positions was greater than 1 mm for moving MLC leaves. Between predicted and delivered positions, the difference was significantly lower, dropping to around 0.25 mm. This is shown below, along with a visualization of planned, delivered, and predicted leaf positions (click for larger versions):

Clearly the predicted positions are closer to the delivered positions than are the planned positions. This is the ideal outcome.

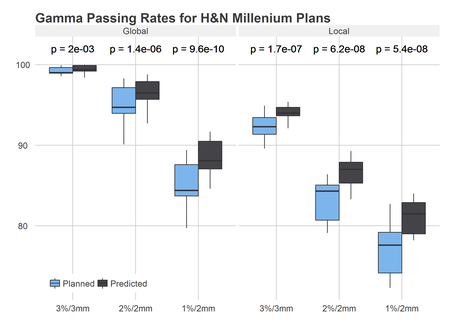

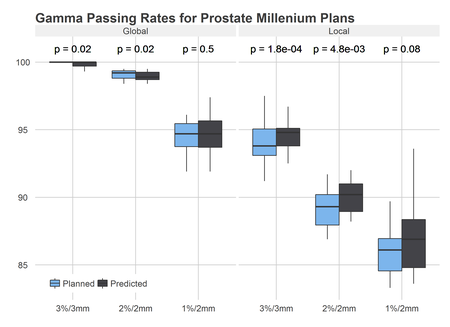

Impact on Gamma Passing Rates

The important question is whether or not these errors can be shown to impact dosimetry. We can explore this by comparing the delivered dose distribution to the distributions calculated by the treatment planning system for both the planned and predicted positions. If correcting for the errors increases the accuracy of the calculated dose distribution, we would expect the gamma passing rate for the predicted dose distribution to be higher than that of the planned distribution.

This is precisely what we see, for all gamma criteria, the predicted positions have a higher passing rate than do the planned positions. Put in other words, the predicted positions are a better representation of reality than are the planned positions. Using the predicted positions increases the accuracy of dose calculation in the treatment planning system.

Impact on Patient Dosimetry

Clearly the predicted positions offer better calculation accuracy than do planned positions. But, does this increase in accuracy impact dose to the patient? That is, is the treatment planned being provided with inaccurate calculation of how much dose is being delivered to critical organs?

By calculating the planned dose, and predicted dose to actual CT scans of head and neck cancer patients, we find that this is the case. Although the differences are not large, many are statistically significant. This calculation was completed with only 5 patients, however the trends are clear. Particularly for organs at risk at the periphery of treatment plans, there are significant differences. Notably, the parotid gland, where the difference between planned and predicted volumes receiving 50% of the dose was, on average, near 10%.

Conclusions

In this study, it was shown that MLC leaf position errors can be predicted to a high degree of accuracy by utilizing statistical learning techniques. All models took only a single plan as an input, the models are simple to implement, and take approximately one second to train. By utilizing the predicted positions to recalculate dose distributions it was shown that gamma passing rates can be increased, and that errors in MLC positions that impact dose volumetric parameters can be reduced. The methodology developed in this study was shown to be generalizable to other institutions by assessing multi-institutional data.

By incorporating and correcting for the predicted errors in MLC positions, optimization routines for encoding MLC leaf positions may be improved, and would allow for more realistic calculation of the dose distributions as truly delivered to the patient.